- About Us

- Columns

- Letters

- Cartoons

- The Udder Limits

- Archives

- Ezy Reading Archive

- 2024 Cud Archives

- 2023 Cud Archives

- 2022 Cud Archives

- 2021 Cud Archives

- 2020 Cud Archives

- 2015-2019

- 2010-2014

- 2004-2009

|

The Strange Fruit that still rots in America’s collective memory |

Recent events in the Deep South have reignited interest in the traditional mystique that has cloaked the region, as well as its troubled place in both past and present U.S history.

Recent events in the Deep South have reignited interest in the traditional mystique that has cloaked the region, as well as its troubled place in both past and present U.S history.

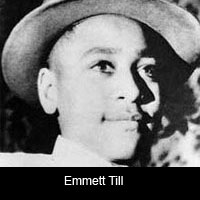

Though always looming large in the history and collective memory of African-Americans, the past two years in the United States have seen a return to prominence and reassessment in the mainstream of the crime of lynching. In May of 2004 the Department of Justice announced that they were reopening their inquiry into the notorious 1955 murder of black teenager Emmett Till given new evidence that the case and trial of his alleged killers had been mishandled at the time. Though accounts still vary as to what exactly transpired, fourteen-year-old Till was murdered while on a trip from Chicago to Mississippi to see family after it was claimed he simply said ‘bye’ or whistled at a white woman in a store. The two men charged in the case, Roy Bryant (the white lady’s husband) and J.W Milam, were acquitted by an all-white jury and later admitted their guilt in a magazine interview. They couldn’t be prosecuted a second time because America’s ‘double jeopardy’ rule of law prevents an individual from being tried a second time where they have already been acquitted for the same offence.

Then in early June 2005 the Senate at long last voted to apologise for their failure over the years to enact an anti lynching law- something that had been repeatedly rejected by conservative and predominantly Southern leaders despite the loud objections of not merely civil rights groups and the embattled, but some seven U.S presidents who had petitioned Congress for the act to become a recognised crime in federal law.

Just such a law would have effectively prevented many of the 4,743 lynchings that the Centre for Constitutional Rights recognises as having taken place in America between 1882 and 1968. This non-binding apology from the Senate obviously came far too late to save these victims, but while the United States had issued formal apologies to citizen groups in the past (such as Japanese-Americans in the wake of war-era internment policies), an apology to African-Americans for previous wrongs had always been considered a treacherous path for the government because of fears it might risk opening the floodgates to those demanding reparations for slavery.

Just such a law would have effectively prevented many of the 4,743 lynchings that the Centre for Constitutional Rights recognises as having taken place in America between 1882 and 1968. This non-binding apology from the Senate obviously came far too late to save these victims, but while the United States had issued formal apologies to citizen groups in the past (such as Japanese-Americans in the wake of war-era internment policies), an apology to African-Americans for previous wrongs had always been considered a treacherous path for the government because of fears it might risk opening the floodgates to those demanding reparations for slavery.

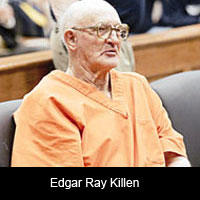

Perhaps in the same spirit of reconciliation that had prompted the Senate’s apology, in Mississippi a few weeks later on June 22 of the same year a man alleged to have led a small mob to commit another lynching of sorts in 1964 was convicted by a jury to a maximum possible sentence of 60 years in prison. 80 year-old Edgar Ray Killen was found guilty on three counts of manslaughter for the brutal killing of civil rights workers James Chaney, 21, Michael Schwerner, 24, and Andrew Goodman, 20, in the so-called ‘Freedom Summer’ murders (the incident was later dramatised in the 1988 movie ‘Mississippi Burning’). The conviction came some forty-one years to the day after the three men had been killed.

Outrage in the wake of the crime famously galvanised the civil rights movement into action and proved to be something of a death-knell for those in the South and elsewhere who continued to restrict and violate the rights and freedoms of African-Americans with free-reign administration of ‘justice’. The case, however, had still remained a sore issue in the minds of many. None of those that were convicted for the crime back in 1964 had remained in prison beyond six years, and Killen had been acquitted by a jury deadlocked 11-1 when the holdout juror claimed she could not convict a preacher, even as Killen – a part-time preacher at that - was also a member of the Ku Klux Klan.

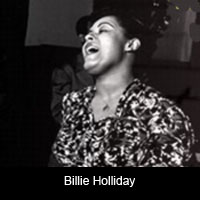

And so it is that a reopening of the Emmett Till case, the Senate’s recent apology for inaction against lynching, and the recent conviction of Edgar Ray Killen hold substantive as well as symbolic significance in the overall landscape of race relations in America. They also bring to mind much of the history and culture of lynching, and foremost in that culture, and the most famous anti-lynching protest song of the era, was Billie Holiday’s 1939 haunting rendition of Strange Fruit.

And so it is that a reopening of the Emmett Till case, the Senate’s recent apology for inaction against lynching, and the recent conviction of Edgar Ray Killen hold substantive as well as symbolic significance in the overall landscape of race relations in America. They also bring to mind much of the history and culture of lynching, and foremost in that culture, and the most famous anti-lynching protest song of the era, was Billie Holiday’s 1939 haunting rendition of Strange Fruit.

Surprisingly, the song was originally written and composed under the pseudonym Lewis Allen by a white Jewish schoolteacher from the Bronx named Abe Meeropol. It is said that Meeropol, a sometime activist, was inspired to pen the song, originally a poem, after reading a magazine article about an especially brutal lynching that had taken place in the South. Performed by various artists without exceptional success, the song was soon brought to the attention Billie Holiday by a manager of the integrated Greenwich Village club Café Society at which she appeared regularly. Her performances of the song –which soon became her noted, regular closing number- created such a stir and generated so much emotion from the audience that she determinedly recorded Strange Fruit for a specialist label even after her own mainstream label had refused to release the song. Driven by the harrowing lyrics, imagery and Holiday’s own unique and memorable style, it was an instant chart success with widespread influence into activist and political circles that cannot be overstated enough.

Lynching’s origins in the United States lay in the eighteenth century Revolutionary War, however it was not until after the American Civil War that it became more specifically directed towards the African-Americans of the South. As a means of maintaining Southern white superiority through extra-legal control over those whom they saw as being inferior, lynching was extremely effective up until the anti-lynching drives of the 1960s.

A pure definition of lynching is difficult, but several key elements were often in place in what might be recognised as a ‘true’ lynching. While lynch mobs were generally spearheaded by a mere handful of conspirators - as in the ‘Freedom Summer’ murders, for instance - in some cases they were joined by crowds numbering into the thousands. Many lynchings recorded in the early twentieth century were a public spectacle despite their ostensible illegality. They were spirited community, family affairs wherein special trains might be organised to transport in the masses of revellers, and postcard photographs of the deceased victims could be sold as souvenirs. One particular Klan-led lynching in Memphis in 1917 attracted 15,000 spectators. Brutalising, at times dismembering their victims, this callous activity was all carried on in the name of preserving the purity and honour of the South from what they saw as oversexed black savages and interventionist Northerners. The guilt or innocence of the victim was rarely as important as the symbolic significance of entrenching a sense of white superiority over another race and perceived threats from such races.

A pure definition of lynching is difficult, but several key elements were often in place in what might be recognised as a ‘true’ lynching. While lynch mobs were generally spearheaded by a mere handful of conspirators - as in the ‘Freedom Summer’ murders, for instance - in some cases they were joined by crowds numbering into the thousands. Many lynchings recorded in the early twentieth century were a public spectacle despite their ostensible illegality. They were spirited community, family affairs wherein special trains might be organised to transport in the masses of revellers, and postcard photographs of the deceased victims could be sold as souvenirs. One particular Klan-led lynching in Memphis in 1917 attracted 15,000 spectators. Brutalising, at times dismembering their victims, this callous activity was all carried on in the name of preserving the purity and honour of the South from what they saw as oversexed black savages and interventionist Northerners. The guilt or innocence of the victim was rarely as important as the symbolic significance of entrenching a sense of white superiority over another race and perceived threats from such races.

Sex was certainly a central principle around which much of the racial segregation and hatred of the period was organised, as many Southerners encouraged the myth of the oversexed and brutal black savage. Such a myth could be a great source of fear among isolated, uneducated Southern communities, and lynchings were often accompanied by the almost ritualistic castration of the black victim as a means of eliminating his source of power and the ‘threat’ that he posed to the community. As difficult as it might be from our modern perspective to comprehend, those Southern whites that were brought up on the ideology of lynching and the myth of the oversexed black savage honestly believed that their method and actions were wholly justified. It was not really until the post World War Two period that significant scrutiny and effective opposition to lynching began, spurred on by the ongoing efforts of such groups as the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP), the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching, and those Southerners themselves who were growing tired of the ugly stereotype that had formed of a ‘typical Southerner’.

At a time when these acts were still freely taking place, Holiday’s Strange Fruit offered a jarring, real description of the truth and irony of lynching in America:

Southern trees bear strange fruit,

Blood on leaves and blood at root,

Black bodies swinging in the Southern breeze,

Strange fruit hangin' from the poplar trees.Pastoral scene of the gallant South,

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouths,

Scent of magnolia, sweet and fresh,

Then the sudden smell of burning flesh.Here is a fruit for the crows to pluck,

For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck,

For the sun to rot, for the trees to drop,

Here is a strange and bitter crop.

Holiday’s eerie rendition when combined with the horrific imagery of Meeropol’s lyrics – Scent of magnolia, sweet and fresh, Then the sudden smell of burning flesh - was hard to ignore. So too was the conflict between the traditional, romanticised views of the gallant South and the almost medieval brutalities of lynching that were such a departure from any conceivable form of chivalry. This was indeed a strange and bitter crop far removed from the supposed ideals of American liberty and democracy.

By the 1960’s the crime of lynching simply could not occur unfettered because the world, now turning their attention to such influential leaders as Martin Luther and Malcolm X, the anti-war movement, and the feminist wave, was a world that could no longer accept an act of lynching, nor the motivations behind it. The ideology had simply advanced far beyond a point of tolerance for something so primitive in nature. But open appraisal and analysis of the crime and the era in which it lived for nearly one hundred years has never truly been reached. It should be noted that a Federal statute against lynching still, to this day, has never been passed. Perhaps as renewed steps toward consolidating and confronting the unanswered questions of lynching continue in the coming months, a new, wide-eyed look at Billie Holiday’s Strange Fruit might remind, encourage and inspire us, to look even further into this most dark period of America’s history.

By the 1960’s the crime of lynching simply could not occur unfettered because the world, now turning their attention to such influential leaders as Martin Luther and Malcolm X, the anti-war movement, and the feminist wave, was a world that could no longer accept an act of lynching, nor the motivations behind it. The ideology had simply advanced far beyond a point of tolerance for something so primitive in nature. But open appraisal and analysis of the crime and the era in which it lived for nearly one hundred years has never truly been reached. It should be noted that a Federal statute against lynching still, to this day, has never been passed. Perhaps as renewed steps toward consolidating and confronting the unanswered questions of lynching continue in the coming months, a new, wide-eyed look at Billie Holiday’s Strange Fruit might remind, encourage and inspire us, to look even further into this most dark period of America’s history.