- About Us

- Columns

- Letters

- Cartoons

- The Udder Limits

- Archives

- Ezy Reading Archive

- 2024 Cud Archives

- 2023 Cud Archives

- 2022 Cud Archives

- 2021 Cud Archives

- 2020 Cud Archives

- 2015-2019

- 2010-2014

- 2004-2009

|

(May 2015) The Ayers Rock Dingo Murders |

(in in memory of Angela Carter and Azaria Chamberlain)

“The world is for thousands a freak show; the images flicker past and vanish; the impressions remain flat and unconnected in the soul. Thus they are easily led by the opinions of others, are content to let their impressions be shuffled and rearranged and evaluated differently (Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe)

Lawyers and painters can soon make what's black, white (Anon.)

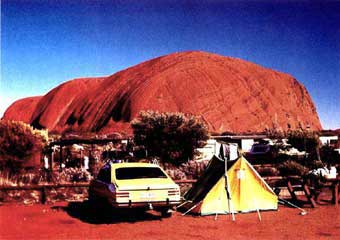

Early in the morning of the seventeenth of August, 1980, in the tent town of Ayers Rock, Northern Territory.

Cool, cool, cool. It is early spring and the dispossessed Northern Australian winter blows its last breath when the sky is clear of cloud and sun. Soon the sun will rise and will do so earlier and earlier as the year beats on so that the tourists will be able to say ‘it’s hot in this part of the world’ and wipe their sodden brows.

Behind the zipped screens of tents campers lie under such a muddle of bags and blankets that they could be refugees; it is difficult to tell where one body starts and another ends. The sleeping bodies have wriggled in the night in search of warmth and now lie still on its discovery, bellowing approval in steamy yawns so that their tents, glistening with morning damp, come to resemble sweaty canvas chimneys.

The pale ancestors of some came to put up house, chimney and church out here in the unplanned but could barely raise a fire, a fact that should give the descendants the smiling satisfaction of the evolved when they wake and contemplate the barbecue that waits.

In another cramped tent on this crisp morning baby Azaria, Blessed of God, preempts her Maker’s huge golden timepiece and cries a little, the unmistakable whimper of a toddler, but soon settles in the warmth of her canvas womb. She will cry once more today, once more into eternity. For now though her penultimate cry is well received. Her Earthly maker, Michael, will kiss this twitching alarm clock as his family stirs and race the sun to Ayers Rock, camera poised.

Lindy Chamberlain is the next piece of the puzzle of sleeping bag and pillow to rise. She sees the space left by her husband, notices his sneakers have left with him and thinks enviously of his boyish energy. The suit of a track star she herself wears this morning is not for such sport; it hides the burdens of motherhood, her surfeited breasts. Every morning the pain of them brings baby back to breast, like Azaria is being born daily, forever new.

It was a good birth all but one anonymous doctor will report. The pregnancy lasted ten months; Lindy Chamberlain sacrificed an extra month for the girl she always wanted: “Boys are such monkeys. Fancy three of them.”

A couple of kilometers away, closer to Maggie Springs, another lot stir. Their father is also awake; it is said he rarely sleeps. The father’s breakfast consists of a bit of water and a good look around. After all, he has his family to feed. Bone-wiry his body and eyes will dart together in search of food, but the signs are getting harder and harder to read, the footprints obscured by the feet of a large predator: Predatorius Homo Sapien. Despite being dispossessed daily of his front yard, father is remarkably calm, even smiling for cameras and piggy-backing a few human kids.

Michael returns to his camp with nearly a full film. His had been one of the cameras firing at the Rock as it rose with the sun. He is a keen photographer but unaware his work will later appear as the dust-jacket on those fictions of public record, the newspapers. Michael Chamberlain won’t supply the captions.

In a camp further down the track with surviving houses, chimneys and churches sleeps Winmaati, Pitjanjatjara man and guide. Winmaati sleeps outside the walls of his house this 8 O’clock. Such numbers matter very little to Winmaati for he does not count in the whitefella way but has a great memory nonetheless.

Winmaati will come to recall more than most, despite a hangover. Yet no matter how long the clock of the whitefella court ticks, he can’t say too much, for he is bound by a timeless law.

Lindy Chamberlain puts on the dark sunnies she will wear through time infinite. Cool sunnies. Killer sunnies. They mask her tiredness and proclaim her travel experience. You see, Lindy Chamberlain knows it will be bright today under the desert sky; she has been here before. Before Michael. Before kids. Before God. The jacket she wears has badges, testimonies to her travels here and elsewhere. The Badges. Lindy Chamberlain will parade them for Judy West, a fellow camper, over breakfast and receive a few enthusiastic “oohs” and “ahs”, especially when she exhibits the two badges she will set aside for her daughter, for when her little Azaria is older. Judy West smiles. She will remember this moment.

Judy West is also well travelled. She is from Esperance, next stop Antarctica. She knows the wilderness and has seen dingoes before, cowering dingoes, which makes it all the more shocking when one latches onto her daughter, Catherine’s arm shortly after breakfast. The First Sighting.

It is an easy but an unforgivable mistake for a media man to assume that all Christian religions proclaim Sunday as the Sabbath. It make sense in a newsworthy way: Christian Man Makes Sacrifice On August Sabbath. It fits. But if Abraham’s faithful sword swayed above his son on a Saturday would this detail prove problematic? Would this fact meet with any journalist’s definition of newsworthiness in the whole of Christendom?

Seventh Day Adventists observe Saturday as the Sabbath, which tells us that Pastor Michael missed Church yesterday. He will say it was because he was on holiday and the custom of his Church for guest pastors to give the sermon would have stripped him of this rare time for rest. Today is clearly Sunday, the day after he missed Church, so Michael will seem even more the encomiast and greater the evangelist in order to suppress the guilt of his truancy, his faith as steady as the Rock he precariously hurtles down to the great delight of fellow tourists and his sons alike.

As for the sons, Aidan and Reagan, what of them? Should children give evidence? No, we’ll pause them racing each other up the Rock, blonde shining in the sun.

Winmaati notices them blonde ones right away and he supposes that white- haired fella prancing around up front is their relation, with his hair like dry grass swaying as he kicks the Rock.

Winmaati knows by now not to expect too much of many whitefellas in terms of their knowledge of the land. He knows from the language that his Pitjantjatjara people have helped travelling whitefellas through his land and given them fig and water. The Pitjantjatjara he means have since passed and now are known by the kunamnara, the “death name”, so he will not refer to them by the name they possessed when alive. Instead, the fluidity of Pitjantjatjara language allows for words to replace these death names so the decreased are not forgotten. How will one bound by such intricacies give the correct testimony at an inquiry for the little one who is no longer, for the one who is kunamnara?

On the other hand, it is taboo to replace or forget the name of a dead whitefella, so they attach their death names to things. Things like street signs and newspaper columns- sometimes on the front page, sometimes for seven years- bear the death name, and things like land, the very same land that conquers them: Lassiter’s land; Lassiter, running out of locals to lead him to water; Lassiter’s lane. Dead End.

Winmaati smiles now as the two boy blonde explorers bound up the rock. However, as we strike them from the evidence, let us turn to what he sees next: a white woman who must be their mother- “the way she looks at them”- holding a tiny baby. This is a first. Even Winmatti’s unbounded memory cannot account for a white woman holding a baby that small out here. See her over there holding the little one, way out here at the Rock, way out here. She holds the baby so close, like Pitantjatjara women who do so for a good reason; they know of babies being stolen.

A map shows that the Chamberlain’s yellow Torana makes its way from the Rock to Maggie Springs this afternoon. When you look at the map of Ayers Rock and Environs, please notice the dotted line the Torana scribes as though there is ink on the tyres, it looks like this- _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _.

Journeys take on so much significance when they are mapped.

On the map, Maggie springs lies between the Chamberlains’ Camp and the Climbing Point of The Rock. Due South of Maggie Springs – and this will remain so for as long as charts survive weathering and tampering – exists a place the Pitjantjara call Bullari. Our map will call it Cut Throat Cave. Dreamtime men had their throats cut daily for dispossessing another tribe of its women. Shout in Cut Throat Cave and your echo takes on a fatal resonance, as does the echo of a playful Koala Bus schoolgirl, a ghastly prelude.

This afternoon Lindy Chamberlain will spot a dingo near Cut Throat Cave, that’s all. The Second Sighting. She will not realise it at this moment, but her simple observation will elucidate the perfect departure for two opposing stories we shall call The Defence and The Crown, otherwise known as The Dingo and the Cut Throat. Our map shows the juxtaposition so clearly; a naught marks the site of the dingo den and X the site of Cut Throat Cave. Naughts and Crosses. Naught or Life.

Lindy Chamberlain, because the infamous are only recognizable if they are addressed with both names – Ned Kelly, Lizzie Borden, Jolly Swagman and now Lindy Chamberlain – is perturbed by the way the dingo is staring at she and Azaria. Its eyes don’t dash about the way of other dingoes she has seen. She turns to a man standing nearby and, to alleviate her anxiety, jokes: ‘that your dog?” The man does not laugh. Lindy Chamberlain will be misunderstood. The dingo keeps staring and sniffing; the smell of babies so pungent.

Pastor Michael is physically tired as he drives his family in the Torana on the dotted line back to the camping ground. The sinewy frame that disguises thirty-eight years is beginning to loosen and gravity is gaining ground. After all, he has already lived five years longer than his Mentor.

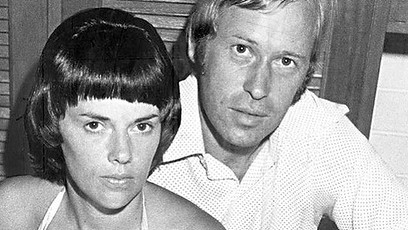

Lindy Chamberlain too is tired, but even still the two of them make a good looking couple. He is blonde, a Christ of Anglo imaginings, while she has dark hair and eyes and figure like a college girl which readily reappears after she gives birth. You might say Lindy Chamberlain is the living embodiment of the idea of rebirth at the centre of her husband’s teachings, a defiant examplar practicing what he preaches. He is the voice, not only preaching to her but for her; his repertoire even extends to answering questions about her pregnancies, so garrulous is he. Pastor Michael would make great talent for television news.

Back at camp the leisured refugees soak up the last of the sun and the wise among them prepare the items they will need for dinner now knowing there is no twilight in these parts; it is either light or dark, never half-light. Things will become hard to see by night and it is under such time constraints that Lindy Chamberlain clips the mouth of baby Azaria to her breast, for the child would be full of warm blood. Blood enough to occupy scientists all over Adelaide, blood enough to cover Azaria’s clothes and parts of a small yellow hatchback, blood for the camera bag, for the tent and shoes, and enough blood to cover the Press of Australia and the rumours, speculations and quips of a nation. Yet no blood is ever to be found on Lindy Chamberlain.

Michael sees a dingo over by the Barbie. The Third Sighting. Aren’t things hard to see at night?

In any other missing persons story you would say that everyone arrives in the correct order; they turn up in descending order of authority: Police; Ranger; Tracker. However, those concerned will want to correct this if they can for as soon as the Policeman arrives he calls for the Ranger who, in turn, calls for the Tracker, who avoids the Policeman so that the narrative cannot even go around in circles like most historical events.

The tourists walk under the trembling light of torches not designed for searches outside their tents and yearn to see daylight and a healthy baby. Now in emu file they see the sand dune between their camping ground and the Rock more clearly than they ever had by daylight. This middle ground now so vital will only make the lower border of their travel photos, a grey periphery which won’t rate a mention at Uncle Geoff’s Slide Night.

Tracker Winmaati receives a tip from a whitefella called Haby about a track Haby has found near the tent and the proper order of events receives another kick in the guts. This is not nearly so violent a kick as when calls are made to newspapers in Adelaide before police Stations in Alice Springs.

You of the Internet Generation won’t remember a time when printed news of an event preceded gossip on the breakfast table. The newsroom of then is now the bedroom and all manner of fingers tap-tap away to the deadline of a better version from a friend. You know these are all only stories don’t you? Yes, but it is best when you’re not sure if they are real: “Hey you” is the headline on your personal memo of truth and summons you to lunge forth into the world SCREAMING the latest. News is merely the afterthought, the already happened, the fish and chip wrapper. With the magic of the story at your command, your keyboard kills of Princesses and your Camera app catches the King with his concubine. How often does the front page or any news for that matter seem utterly remarkable, like nothing you could have predicted? When were you last stopped in your stride by a headline?

In those days, however, the newspaper was the daily Bible: the Bible when we didn’t doubt the Bible; the Bible in thirty seven and one sport pages. The Adelaide News had four editions, like the four gospels. On this Monday, it is Mark that has the businessmen burping with intrigue at the head of their breakfast tables in Glenelg, even before the first dingo joke could be bandied about.

In the ledger of a document that resembles a guest book – a sure sign that the pale ancestors trod the land in vain as it is only the third of its kind in over a century – a teenage Alice Lynne scribbles her name alongside that of her mother and preacher father. How disappointing it is that the trip to Ayers Rock is reduced to a bunch of letters in a book; not nearly the stuff of beating hearts, uplifted heads and the squint of eyes unaccustomed to such penetrating light. Alice shapes the letter carefully, trying to make each one represent one of those feelings, but inevitably fails. She shuts the book and prays she will return.

The trip to Ayers Rock is not the return for which she prayed as they have come from the desert town of Mt. Isa where Michael, in the spirit of Dowsing known in his church, had them move to see if he could extract a bit of Holy Water. They have come from one desert to another and many will wonder why.

Good son Michael, of Abel Smith Street, Mt. Isa, is used to being calm in the face of adversity and although he would like to show the world his bitter-sweet joy at the certain salvation of Azaria by his Maker, he rightly suspects the world might confuse that emotion. Instead he turns his face from the blackened sky to the black box of the Maker of news. In Channel 7 we trust.

Meanwhile, on a Hills Hoist four dingoes hang, their trials abandoned.

Hailing from Sydney’s northern beaches and later the Far North Coast of NSW and Gold Coast, Christopher W. Harris is a permanently travelling expat in Singapore where he is Head of School, Kaplan. He resides there with his teacher wife, Sarah, daughter, Grace (40 stamps on her 5 year old passport) and son, Angus “Chook” Harris, born in Malaysia (30 on his 3 year old passport ). Reading The Cud is his link to home.

Bibliography

Allen, C. (1996) Following Djuna: Women Lovers and the Erotics of Loss. Bloomington, USA: Indiana University Press

Barnes, J. (1989) A History of the World in 10 ½ Chapters. New York: Vintage

Bryson, J. (1985) Evil Angels. Victoria, Australia: Penguin

Buckley, S. (1991) Dowsing Dilemma. Wagga Wagga, Australia: self-published

Carter, A. (1995) The Fall River Axe Murders, from Burning Your Boats, London: Chatto and Windus

Chamberlain, L. (1990) Through My Eyes. Victoria: William Heinemann

Crispin, K. (1987) The Crown Versus Chamberlain 1980-1987. Sydney: Albatross

Damsteegt, P. (1977) Foundations of the Seventh-Day Adventist Message and Mission. Michegan: William B. Eerdmans

Finney, J. (1999) Fictualising the Factual, Retrieved from: www.csulb.edu/~bhfinney/Barnes.html

Gasiorek, A. (1995) Post-War British Fiction, London: Hodder Headland

Hilliard, W. (1968) The People in Between – The Pitjantjatjara people of Ernabella. Suffolk: Hodder and Stoughton

Hudson, L. (1974) Dingoes Don’t Bark. Sydney: Rigby

Morling, T. TRH (1987) Report of the Commissioner into the Chamberlain Convictions

Wright, S. (1968) The Way of the Dingo. Sydney: Angus and Robertson